What Rich People Buy (Assets vs. Liabilities)

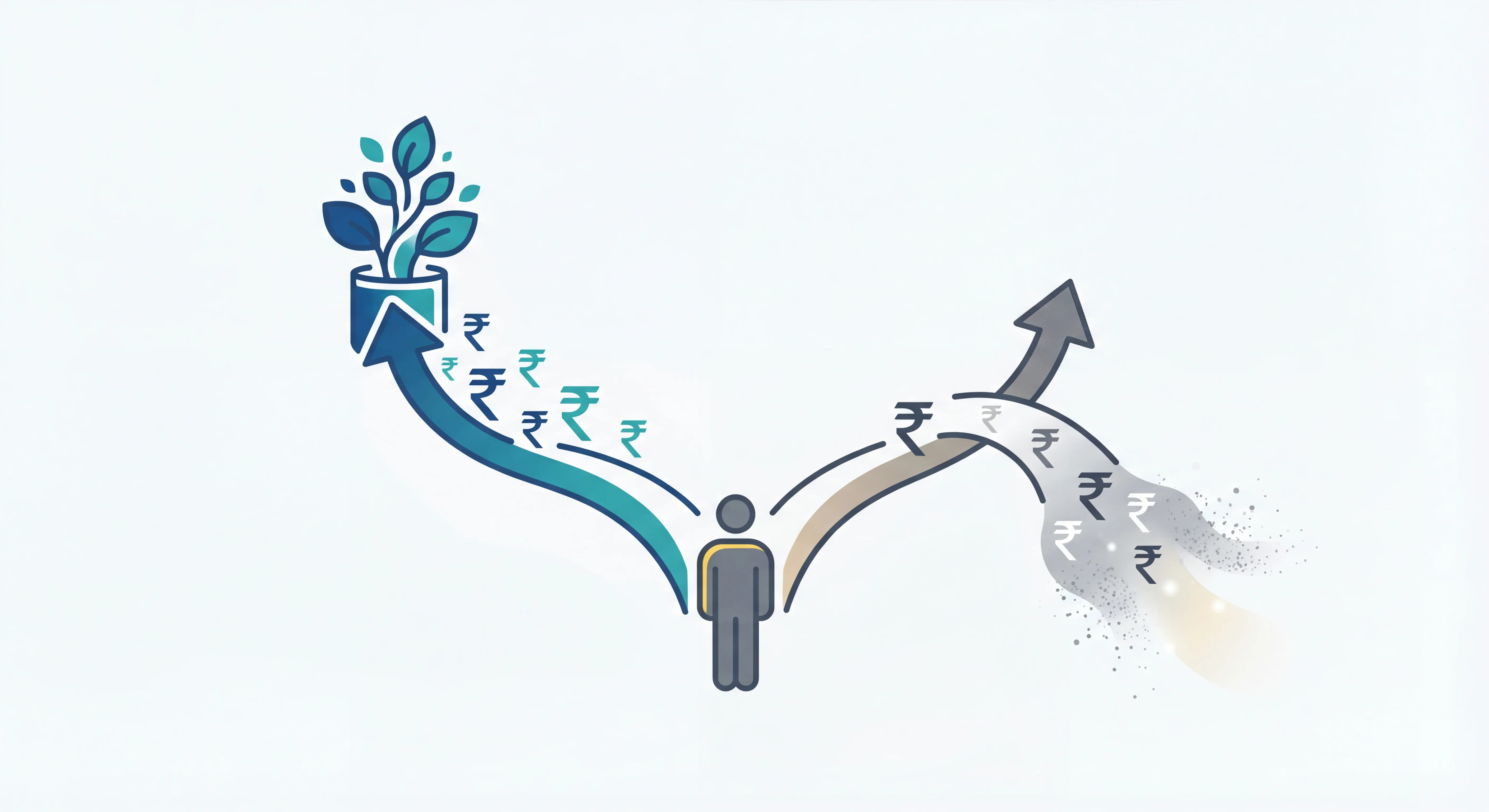

Why some people build wealth while others don't. Understanding the simple distinction between what puts money in your pocket and what takes it out.

TL;DR: How to Think Differently

- Rich people and everyone else buy the same things—they just think about those things differently before, during, and after the purchase

- An asset puts money in your pocket; a liability takes money out — this distinction has nothing to do with what society calls "valuable"

- Most things marketed as investments are actually liabilities dressed in respectable clothing

- The question isn't "Can I afford this?" but "What will this cost me over time?" — the purchase price is just the entry fee

- Wealth isn't built by earning more—it's built by keeping the money flowing in the right direction toward things that generate, not consume

- Looking rich and being rich require opposite strategies — one is about spending on depreciating items, the other is about accumulating appreciating ones

Who This Is For

This is for anyone who has ever wondered why they're working hard, earning decently, but not building wealth.

If you've looked at your bank balance and your possessions and felt confused about why the numbers don't match the effort, this is for you. If you've bought things that seemed like good investments but somehow increased your financial stress instead of reducing it, this is for you. If you've noticed that people who earn less than you seem more financially stable, this is for you.

This is especially for people who've been told that owning things—a car, property, gold—makes you wealthy, but haven't felt wealthier despite owning them.

You're not doing it wrong. You're just operating with a definition of wealth that doesn't match how wealth actually works.

The Tale of Two Uncles

Let me tell you about two people I'll call Uncle A and Uncle B.

Uncle A earns ₹18 lakhs a year. He drives a ₹15 lakh car (on EMI). He lives in a good apartment (rented, but in a nice area). He wears branded clothes. He takes his family on international vacations. He recently bought a ₹3 lakh Rolex because "it holds value."

Uncle B earns ₹16 lakhs a year. He drives a 7-year-old Maruti. He lives in a modest 2BHK he owns outright. He wears regular clothes from reasonable brands. He takes domestic vacations. He doesn't own expensive watches.

Who looks richer? Uncle A.

Who is actually building wealth? Uncle B.

Because Uncle A's life requires a constant inflow of money to sustain. The car has EMI + insurance + maintenance. The apartment rent is high. The lifestyle is expensive. The watch doesn't generate income—it just sits there being expensive.

Uncle B's life generates small surpluses every month. The paid-off apartment means no rent or EMI. The old car has minimal costs. The modest lifestyle keeps expenses low. He invests those surpluses.

In 10 years, Uncle A will have nicer things and the same level of financial stress.

Uncle B will have options.

This is the difference between buying liabilities and buying assets.

What These Words Actually Mean

Let's strip away all the complexity and start simple.

An asset is something that puts money in your pocket.

A liability is something that takes money out of your pocket.

That's it. That's the whole distinction.

Not "what society values." Not "what might appreciate someday." Not "what makes you look successful."

Just: does money flow toward you, or away from you?

Assets (Money Flows In)

- A rental property that generates ₹20,000/month after all expenses

- Shares of a company that pay dividends

- A fixed deposit that pays interest

- A mutual fund that grows over time

- A skill that people pay you for

- A small business that generates profit

Liabilities (Money Flows Out)

- A car (fuel, insurance, maintenance, depreciation, EMI)

- The house you live in (maintenance, taxes, society charges—yes, even your own home)

- Designer clothes (they lose value the moment you buy them)

- Gold jewellery (storage cost, no income, emotional value only)

- Expensive watches, gadgets, furniture

- Subscriptions that auto-renew

Notice what's missing from the liability list: judgment.

A car isn't bad. Your home isn't bad. Nice clothes aren't bad.

But they're not assets. They're costs. They take money out.

The problem isn't owning liabilities. It's thinking they're assets.

The Direction of Cash Flow

Here's the mental model that changes everything.

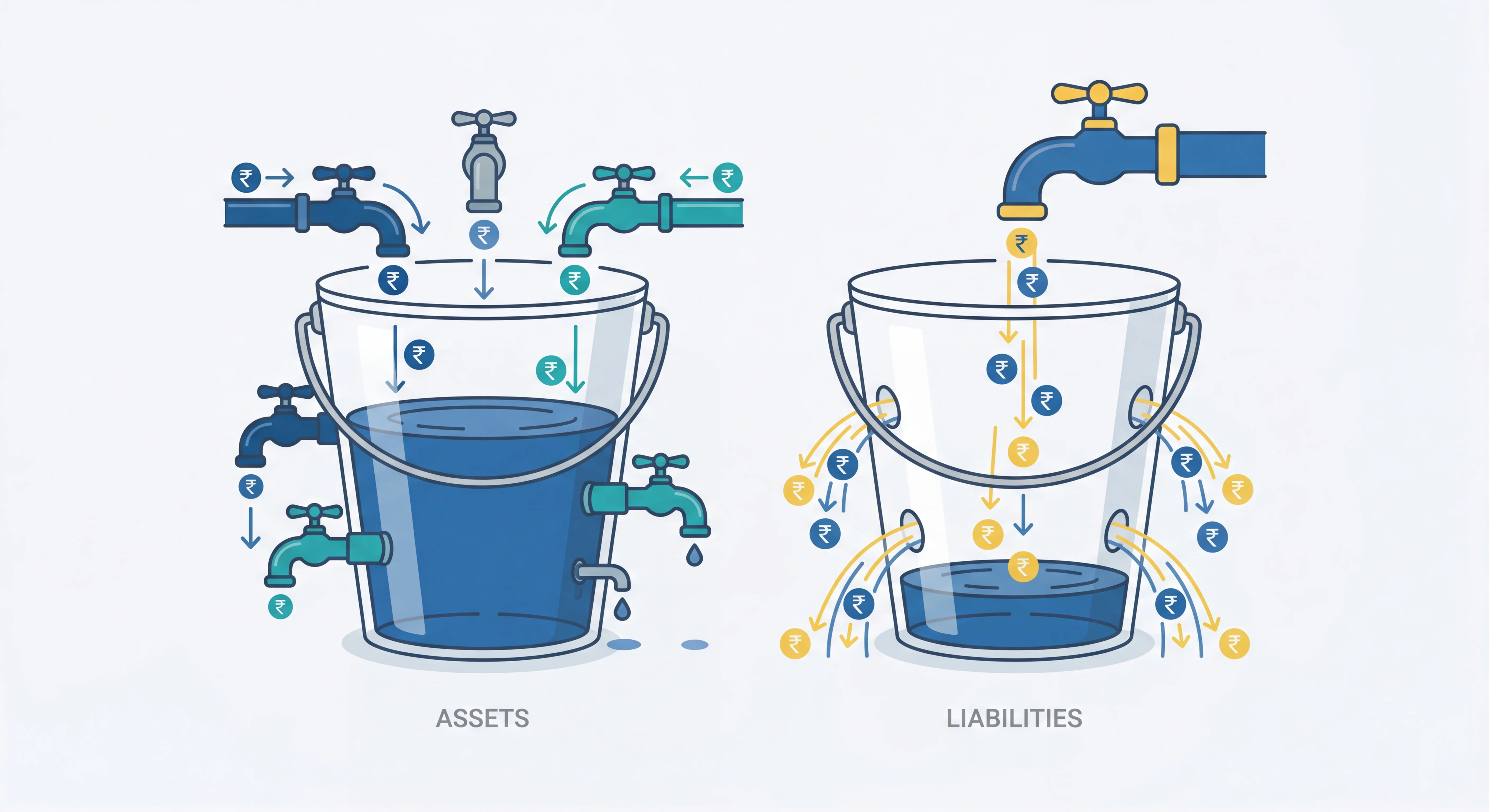

Imagine your financial life as a bucket with holes in it.

Assets are taps that pour water into the bucket.

Liabilities are holes that let water leak out.

Your salary is water being poured in from the top.

Now, most people focus only on the salary tap. "If I just get a bigger tap (higher salary), my bucket will fill up."

Except they keep drilling more holes. Bigger car (bigger hole). Bigger house (bigger hole). More lifestyle (more holes).

The bucket never fills because the holes expand as fast as the tap.

Rich people think differently. They focus on two things:

- Adding more taps (buying assets that generate income)

- Plugging unnecessary holes (minimizing liabilities)

They're not worried about the salary tap being bigger. They're building a system where the bucket fills automatically.

The House Confusion

This is where people get most confused, so let's address it directly.

Your house—the one you live in—is not an asset.

"But it's worth ₹80 lakhs! How is that not an asset?"

Because it's taking money out of your pocket every month, not putting money in.

Property tax. Maintenance. Society charges. Repairs. If you have a home loan, add EMI and interest.

Money flows out. Every month.

"But the value is increasing!"

Maybe. But you can't eat that increase. You can't pay bills with it. It's locked up.

As long as you're living in it, it's not generating income—it's consuming it.

The house you live in is a liability you're choosing to own instead of rent. That can be a good choice for many reasons (stability, forced saving, long-term appreciation). But it's not an asset in the cash-flow sense.

Now, a second property you rent out? That's an asset. Money flows in.

Same physical thing. Different purpose. Different classification.

What People Actually Buy

Let's look at common Indian purchases through this lens:

The Car

You buy a ₹12 lakh car.

Day 1: It's worth ₹10 lakhs (the moment you drive it out).

Every month: ₹15,000 EMI + ₹5,000 fuel + ₹1,500 insurance (monthly average) + ₹2,000 maintenance = ₹23,500 out.

Every year: The car loses ₹1-1.5 lakhs in value (depreciation).

This is a liability. Not because cars are bad, but because money flows out.

Gold Jewellery

You buy ₹5 lakhs worth of gold jewellery.

Making charges: You paid ₹5 lakhs but it's worth ₹4.3 lakhs if you sell it immediately.

Storage: Locker rent or worry about safety.

Income: Zero.

Appreciation: Maybe gold prices rise 6% a year. Inflation is also 6%. You're breaking even in purchasing power, at best.

This is a liability posing as an asset.

Real Estate (Primary Home)

You buy a ₹60 lakh flat with a ₹45 lakh loan.

EMI: ₹40,000/month for 20 years.

Interest over 20 years: ₹51 lakhs (you'll pay ₹96 lakhs total for a ₹60 lakh flat).

Maintenance: ₹3,000/month.

Money out every month: ₹43,000.

Money in: Zero.

Liability. A necessary one for many people, but still a liability.

Rental Property (Investment)

You buy a ₹50 lakh apartment in a smaller city and rent it out.

Loan EMI: ₹35,000/month.

Rental income: ₹25,000/month.

Net: You're paying ₹10,000 out of pocket every month.

"Wait, that's still a liability!"

Yes. For now. But here's the difference:

In 20 years, the loan is paid off. The tenant is now paying you ₹60,000/month (assuming rental appreciation). Plus, the property might be worth ₹1.2 crores.

This is a liability that transforms into an asset. Money flows out initially, but the direction reverses.

Mutual Funds / Stocks

You invest ₹10,000/month in equity mutual funds.

Money out: ₹10,000/month.

Money in (eventually): Dividends, capital appreciation.

"But I'm putting money in, not getting money out!"

True. But here's the distinction: this money is working for you. It's not gone—it's transformed. It's buying you ownership in businesses that generate profit.

This is an asset-in-formation. Initially it feels like money out, but its actually money repositioned to grow.

What People Get Wrong

"I need a car, so it's not a liability—it's necessary"

Necessary and liability aren't opposites.

You might absolutely need a car for your work or family. That's fine. But it's still taking money out of your pocket.

The mistake is thinking "necessary" means "not a cost."

A necessary liability is still a liability. You just have good reasons for accepting it.

"Gold is always a good investment"

Gold is good for preserving wealth across generations. It's good as a hedge against currency collapse. It's good for liquidity in emergencies.

But it's not an investment in the cash-flow sense. It doesn't pay you dividends. It doesn't generate rental income.

Gold is insurance, not an asset.

"My house will double in value in 10 years"

Maybe. If you're in the right location. If the economy grows. If real estate doesn't stagnate like it did in many Indian cities from 2014-2020.

But even if it does double, two problems:

- You can't access that value while living in it

- Inflation might also double the price of the next house you'd want to buy

Appreciation is good. But it's not the same as cash flow.

"Rich people buy expensive things, so expensive things make you rich"

This is the most dangerous confusion.

Rich people buy expensive things after they've built assets that generate income.

They buy the ₹50 lakh car from the passive income their ₹10 crore portfolio generates.

The car didn't make them rich. The portfolio did. The car is a reward, not a strategy.

When you reverse this—buy the expensive things first, hoping to build wealth later—you've just locked yourself into a high-expense lifestyle that prevents wealth accumulation.

"I can afford the EMI, so I can afford it"

You can afford the monthly payment. That's not the same as affording the total cost.

A ₹12 lakh car on a 5-year loan at 9% interest means you'll pay ₹14.9 lakhs.

Plus, insurance: ₹3 lakhs over 5 years.

Plus, fuel: ₹3 lakhs over 5 years (conservative).

Plus, maintenance: ₹2 lakhs over 5 years.

Total: ₹22.9 lakhs for a ₹12 lakh car.

And at the end, the car is worth ₹4 lakhs.

You can afford the ₹25,000/month EMI. But can you afford ₹18.9 lakhs of value destruction?

How to Think About This Going Forward

The Income-Generation Test

Before buying something significant, ask:

"Will this put money in my pocket, or take money out?"

If it takes money out, it's a liability. Now ask the second question:

"Do I have enough assets already that can cover this liability?"

If your investments generate ₹30,000/month passively, and the car costs ₹25,000/month to own, you can afford it.

If your salary is ₹80,000/month and the car costs ₹25,000/month, you're using active income (your time and effort) to pay for a depreciating item.

Different equations. Different outcomes.

The Opportunity Cost Lens

Every ₹10,000 you spend on a liability is ₹10,000 you didn't invest in an asset.

₹10,000/month in a car EMI over 5 years = ₹6 lakhs paid.

₹10,000/month invested in equity mutual funds over 5 years at 12% return = ₹8.2 lakhs accumulated.

The car costs you ₹6 lakhs. The investment gives you ₹8.2 lakhs. The gap is ₹14.2 lakhs.

That's the real cost of the car—not just what you paid, but what you didn't build.

The Reversal Strategy

You can't avoid all liabilities. Life requires some of them.

But you can sequence them differently:

Common approach: Buy liabilities first (car, house, lifestyle), then try to build assets with whatever's left over.

Result: Nothing's left over. Assets never get built.

Reversal approach: Build assets first (investments, rental income, business equity). Then buy liabilities with the cash flow those assets generate.

Result: Liabilities don't hurt because assets cover them.

The reversal is uncomfortable because you delay gratification. But it's the only math that works.

The Maintenance Multiplier

When evaluating a purchase, don't just look at the price tag.

Multiply by the maintenance factor:

- Car: 1.5-2x the purchase price over its lifetime in running costs

- House: 1-2% of property value per year in maintenance

- Luxury watch/jewellery: Insurance, storage, opportunity cost of capital

A ₹3 lakh watch isn't a ₹3 lakh decision. It's a ₹3 lakh decision plus the lost opportunity to invest that ₹3 lakhs, which at 12% growth over 10 years would become ₹9.3 lakhs.

What This Connects To

This asset-liability distinction is the foundation of every other wealth-building concept you'll encounter.

It explains why budgeting matters—you're trying to create surplus that flows toward assets, not liabilities.

It explains why investing is necessary—salary alone is just one tap; you need multiple income streams.

It explains why early retirement is possible for some—they've built enough asset taps that their bucket fills without them working.

Later, you'll learn to measure net worth (assets minus liabilities). You'll learn about cash flow management. You'll learn about debt—good debt builds assets, bad debt funds liabilities.

But everything traces back to this simple question: Is money flowing toward me or away from me?

Once you start seeing your financial life through this filter, your decisions change automatically.

Not because you're depriving yourself.

But because you've shifted from asking "Can I afford this?" to asking "What will this cost me in terms of assets I won't build?"

The Shift in Thinking

Rich people aren't smarter. They aren't more disciplined. They don't have better willpower.

They just ask a different question when they see something they want to buy.

Poor question: "Can I afford this?"

(If the EMI fits in your monthly budget, the answer is yes, so you buy it.)

Better question: "What is this, really?"

(An asset that will generate income? Or a liability that will consume it?)

Best question: "If I buy this liability, what asset am I not buying instead?"

The third question changes everything.

Because it forces you to see the trade-off.

The ₹15 lakh car or 15 years of ₹10,000/month SIP that becomes ₹42 lakhs.

The ₹3 lakh vacation or a down payment on a rental property.

The ₹50,000 watch or 5 months of building an investment portfolio.

None of these choices are wrong. But only one set builds wealth.

This isn't about deprivation. It's about direction.

Your money is moving either way. The question is: where?

Toward things that grow, or toward things that decay?

Toward cash flow in, or cash flow out?

Toward building options, or building dependencies?

The wealthy have simply chosen a different direction.

Not because they're better people.

But because they understood this distinction earlier, and let it guide their choices longer.

You don't need to become them.

You just need to see what they saw.

Actionable

The Personal Balance Sheet Audit

This exercise helps you see your current financial life through the asset-liability lens.

Observation List:

- 1List your major possessions/purchases

- 2The Cash Flow Test

- 3Calculate the flow

- 4The revelation

Step 1: List your major possessions/purchases

On a piece of paper or in your phone notes, write down everything significant you own or pay for:

- The house/apartment you live in

- Any other property you own

- Your car(s)/vehicle(s)

- Major investments (mutual funds, stocks, FDs, PPF, gold)

- Significant monthly expenses (EMIs, rent, subscriptions)

- Major purchases in the last 2-3 years over ₹20,000

Step 2: The Cash Flow Test

For each item, ask one simple question:

"Does this put money IN my pocket or take money OUT?"

Mark it:

- IN = Asset (generates income, dividends, rent, profit)

- OUT = Liability (costs money monthly/annually to own or maintain)

- NEUTRAL = One-time purchase, no ongoing cost, no income

Step 3: Calculate the flow

For each "OUT" item, roughly estimate the monthly outflow:

- Car: EMI + fuel + insurance + maintenance

- House you live in: EMI or rent + maintenance

- Subscriptions: Netflix + gym + apps

- Other liabilities: actual monthly cost

Add them up. This is your monthly liability drain.

For each "IN" item, estimate the monthly inflow:

- Rental property: rent minus EMI and maintenance

- Investments: average monthly dividends or growth (even if unrealized)

- Side business: monthly profit

Add them up. This is your monthly asset income.

Step 4: The revelation

Compare the two numbers:

Asset income: ₹_______ Liability drains: ₹_______

Now ask yourself:

-

Is your asset income greater than your liability drain? (If yes, you're building wealth. If no, you're dependent on salary.)

-

What percentage of your major purchases over the last 3 years were liabilities versus assets?

-

If you lost your job tomorrow, would your assets cover your liabilities, even partially?

-

Looking at your next planned major purchase—is it an asset or liability?

The uncomfortable insight:

Most people discover that 80-90% of their money has flowed into liabilities, and only 10-20% into assets.

That's not a moral failing. It's just what happens when you don't have this framework.

But now you do.

LEARNING OUTCOME

This exercise builds the foundational skill of seeing your financial life through cash flow direction rather than social value. Most people evaluate purchases based on what society says is valuable ("a car is important," "own your home," "gold is safe") without asking whether money flows in or out. This audit reveals the gap between what you thought you were building (wealth through possessions) and what you actually built (a high-maintenance lifestyle that requires constant income). The insight isn't "you did it wrong"—it's "here's what's actually happening." Once you see that your asset column is thin and your liability column is thick, future purchase decisions change automatically. You start asking "Will this add to the IN column or the OUT column?" before asking "Can I afford the EMI?" This is the shift from looking wealthy to becoming wealthy.

Smit Panchal

Chartered Accountant | Writing about Money, Clearly

Smit simplifies complex money concepts through first-principles thinking and real-world insights. Writing on personal finance, wealth frameworks, and financial clarity—beyond noise, products, and hype. Views expressed are personal and educational.

Connect on LinkedIn