Why Your Salary Disappears by Month-End

Understand why salary feels gone by month-end. The money was already committed before arrival—learn the gap between what arrives and what's available.

TL;DR: How to Think Differently

- Your salary doesn't disappear—it was already committed before it arrived in ways you've stopped noticing

- The money you think you have and the money actually available to you are two different numbers separated by obligations you've forgotten about

- "This month will be different" is a story you tell yourself every month because you're measuring from the wrong starting point

- Most of your salary gets spoken for in the first week through fixed commitments, then the rest evaporates through the illusion of having more than you do

- The real problem isn't spending too much—it's overestimating how much was ever yours to spend in the first place

- Everyone feels like they should have more left over because they're mentally counting from gross salary, not from what remains after the non-negotiables

Who This Is For

This is for anyone who has ever felt genuinely confused about why there's so little money left when the next salary is about to arrive.

If you earn what feels like a reasonable amount but are somehow always scraping by at month-end, this is for you. If you've promised yourself you'll save "this month" for six months running and haven't, this is for you. If you look at your bank balance on the 27th and feel a quiet panic, this is for you.

This is especially for people who feel like they're not even spending on anything extravagant, yet the money still vanishes.

You're not irresponsible. You're not uniquely bad at this. You're operating with incomplete information about your own financial reality, and that incomplete picture is what's causing the confusion.

The Monthly Optimism Cycle

Here's how it usually goes:

Salary day arrives. Your account shows a number—let's say ₹75,000. For about six hours, maybe a full day, you feel okay. Comfortable. Safe.

You think, "This month, I'll definitely save."

By day three, rent is gone (₹20,000). By day five, EMI auto-deducted (₹15,000). By day seven, credit card bill paid (₹12,000). By day ten, you've covered insurance, phone bills, subscriptions, the maid, the driver, groceries for the week.

By day 12, you're sitting at ₹18,000 remaining. And you still have 18 days to go.

This is when the problem becomes visible, but the problem didn't start on day 12. It started on day 1.

On day 1, when you saw ₹75,000 in your account, your brain registered that as "money I have." But you didn't have ₹75,000. You had ₹18,000. The rest was already committed—you just hadn't paid it out yet.

The salary disappeared before it arrived. You just didn't know it yet.

What "Disappearing" Actually Means

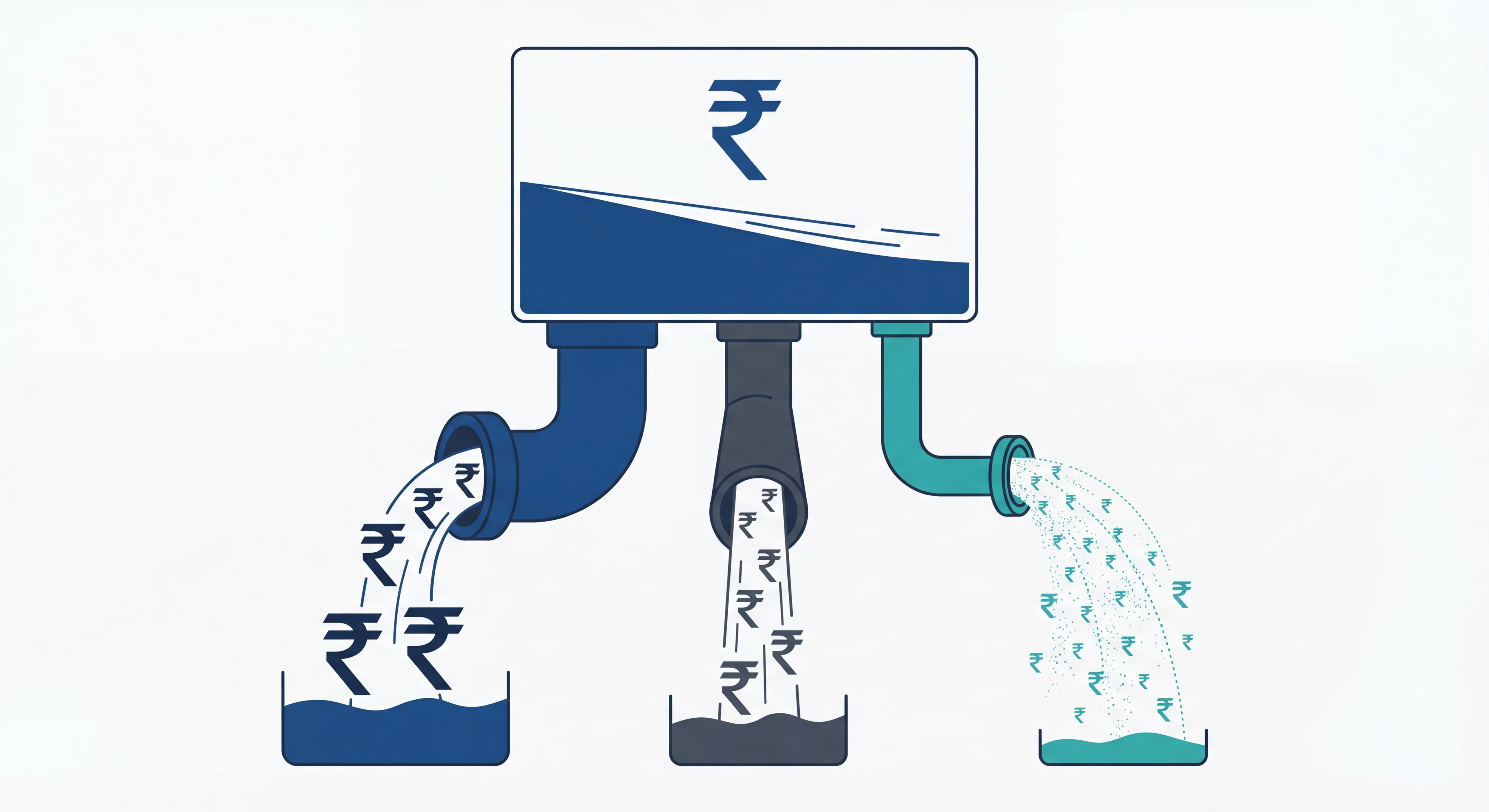

Let's be precise about what's happening here.

Your salary doesn't vanish mysteriously. It leaves through three distinct channels, at three different speeds, and with three different levels of visibility.

Channel 1: The Instant Departures (Days 1-7)

These are your non-negotiables. Rent. EMIs. Credit card bills. Insurance premiums. Loan payments.

You know about these. You expect them. You've mentally accepted them.

But here's what's interesting: you still count them as part of your salary when it arrives.

When ₹75,000 hits your account, your brain doesn't automatically subtract the ₹47,000 that's already committed. It sees ₹75,000 and thinks "I have this much."

You don't. You never did.

The moment your salary lands, ₹47,000 of it is already someone else's. The bank's. The landlord's. The insurance company's. It's just waiting in your account temporarily before moving to where it was always going to go.

This creates a false sense of abundance that lasts exactly as long as it takes for the committed payments to process.

Channel 2: The Predictable Expenses (Days 8-20)

These are things you need to spend on, but they don't happen on a fixed date. Groceries. Fuel. Phone recharge. Electricity bill. Kids' school supplies. Medicine. House help salaries.

You know these are coming. But because they don't have a fixed date, you don't subtract them mentally on day 1.

So, after the committed payments go through and you're sitting at ₹28,000, your brain still thinks "I have ₹28,000 for the rest of the month."

But you don't. You have maybe ₹15,000. The other ₹13,000 is going to groceries, bills, and necessary household spending.

The problem is these feel more "optional" because you control the timing, even though they're not optional at all.

Channel 3: The Everything Else (Days 1-30)

This is where things get messy.

Weekend outings. Ordering in. Cab rides. Coffee with a friend. An online purchase. A book. New headphones because the old ones broke. A birthday gift. Eating out because you were too tired to cook.

None of these individually feel significant. Each one feels justified. Each one is a small decision in the moment.

But in aggregate, across 30 days, this channel absorbs whatever's left after channels 1 and 2.

And because you've been operating under the illusion that you had ₹75,000 when you actually had ₹15,000, every single discretionary expense feels affordable. Until suddenly it's not.

The Timing Illusion

Here's something most people don't realize: the order in which money leaves matters more than you think.

Imagine two scenarios:

Scenario A: Your salary is ₹75,000. Rent, EMIs, and bills (₹47,000) get deducted immediately on day 1, automatically. You never see that money. Your account shows ₹28,000 from day 1.

Scenario B: Same salary, same expenses. But they don't auto-deduct. They sit there for a week while you manually pay them. Your account shows ₹75,000 on day 1, then ₹28,000 by day 7.

Same money. Same obligations. But scenario B feels different.

In scenario B, you experienced having ₹75,000, even if only briefly. Your brain registered abundance. And that registration creates spending behaviour.

When you see ₹75,000 for even a few days, you unconsciously calibrate your spending to that number, not to the ₹28,000 that was actually available.

So, you might order food twice in that first week. Take a cab instead of the metro. Buy something small online. None of it feels irresponsible because "you just got paid."

But that early-month spending is coming from money that was never discretionary. You've just created a sequence that makes it feel discretionary.

This is why people who get paid at the beginning of the month often struggle more than people who get paid mid-month. The mid-month salary arrives when you're already aware of scarcity, so you treat it more carefully.

What You're Actually Experiencing

Let's talk about what's really happening psychologically.

The Gross-vs-Net Confusion

When someone asks what you earn, you probably say ₹75,000 (or whatever your CTC or gross is). That's the number you identify with. That's your salary.

But that's not what arrives in your account.

After PF, professional tax, TDS, and other deductions, maybe ₹68,000 actually lands. You've already "lost" ₹7,000 you never saw.

But you're still mentally calibrated to ₹75,000. So, from day 1, you're already living with a phantom ₹7,000 that doesn't exist.

The Committed-Money Blindness

After rent, EMIs, and bills, you're down to ₹28,000 (from the ₹68,000 that actually arrived).

But you don't experience this as "I have ₹28,000 for 30 days."

You experience it as "I just paid ₹40,000 worth of bills, that was exhausting, now I deserve to relax."

The act of paying bills feels like work, so your brain wants a reward. But the reward comes from the same pot of money that needs to last the month.

The This-Month-Is-Different Delusion

Every month, something happens. Diwali. A wedding. A birthday. A medical emergency. The car breaks down. Your phone screen cracks.

And every month, you tell yourself: "Okay, this month was unusual. Next month will be normal and I'll save."

But there's no such thing as a normal month.

Life happens every month. The "unusual" expense is actually the usual.

What you're calling unusual is just life's baseline variation. The only unusual thing would be a month where nothing unexpected happened.

The Payday Spike

Studies show that people spend more in the 3-4 days immediately after payday than at any other time in the month.

Why? Because money feels abundant. The account is full. The psychological scarcity hasn't set in yet.

So, you say yes to things you'd say no to on day 23. You order in instead of cooking. You take a cab instead of public transport. You buy something you've been eyeing.

Each decision is small. But the pattern of elevated spending in the payday window uses up money you're going to desperately need by day 25.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

"I'm just bad with money"

No. You're working with a mental model that doesn't match reality.

You think you have ₹75,000. You actually have ₹15,000. Of course, you feel like you're failing—you're trying to make ₹75,000 worth of decisions with ₹15,000 worth of resources.

The problem isn't your character. It's your starting assumption.

"If I just earned more, this wouldn't happen"

This is the most persistent myth.

When you earn ₹50,000, you think ₹75,000 would solve everything. When you earn ₹75,000, you think ₹1,00,000 would solve everything.

But here's what actually happens when income increases: committed expenses increase too.

Rent goes up (you move to a better place). EMI goes up (you buy a car or a bigger house). Lifestyle expenses go up (better groceries, more eating out, nicer clothes).

The ₹75,000 pattern recreates itself at ₹1,00,000. Just with bigger numbers.

Income growth doesn't solve this unless you also fix the awareness gap.

"This month I'll definitely save"

You've said this before. You'll say it again.

And you mean it when you say it. On day 1, with a full account, it feels completely achievable.

But you're making a promise based on ₹75,000. And you're going to try to keep it with ₹15,000.

The gap between the promise and the reality is where the monthly disappointment lives.

"At least I'm not overspending"

Technically true. You're not spending more than you earn.

But you're not accumulating anything either. And that creates a very specific kind of financial fragility.

One disruption—a job loss, a medical emergency, an unexpected expense—and you're in trouble. Because there's no buffer. There never has been.

"I'll figure it out next month"

Next month is the same as this month.

Same salary. Same rent. Same bills. Same life.

The only thing that changes next month is that you're 30 days older and still wondering why the money disappeared.

"Next month" is a fantasy where your circumstances magically improve without you changing anything.

Thinking Differently About This

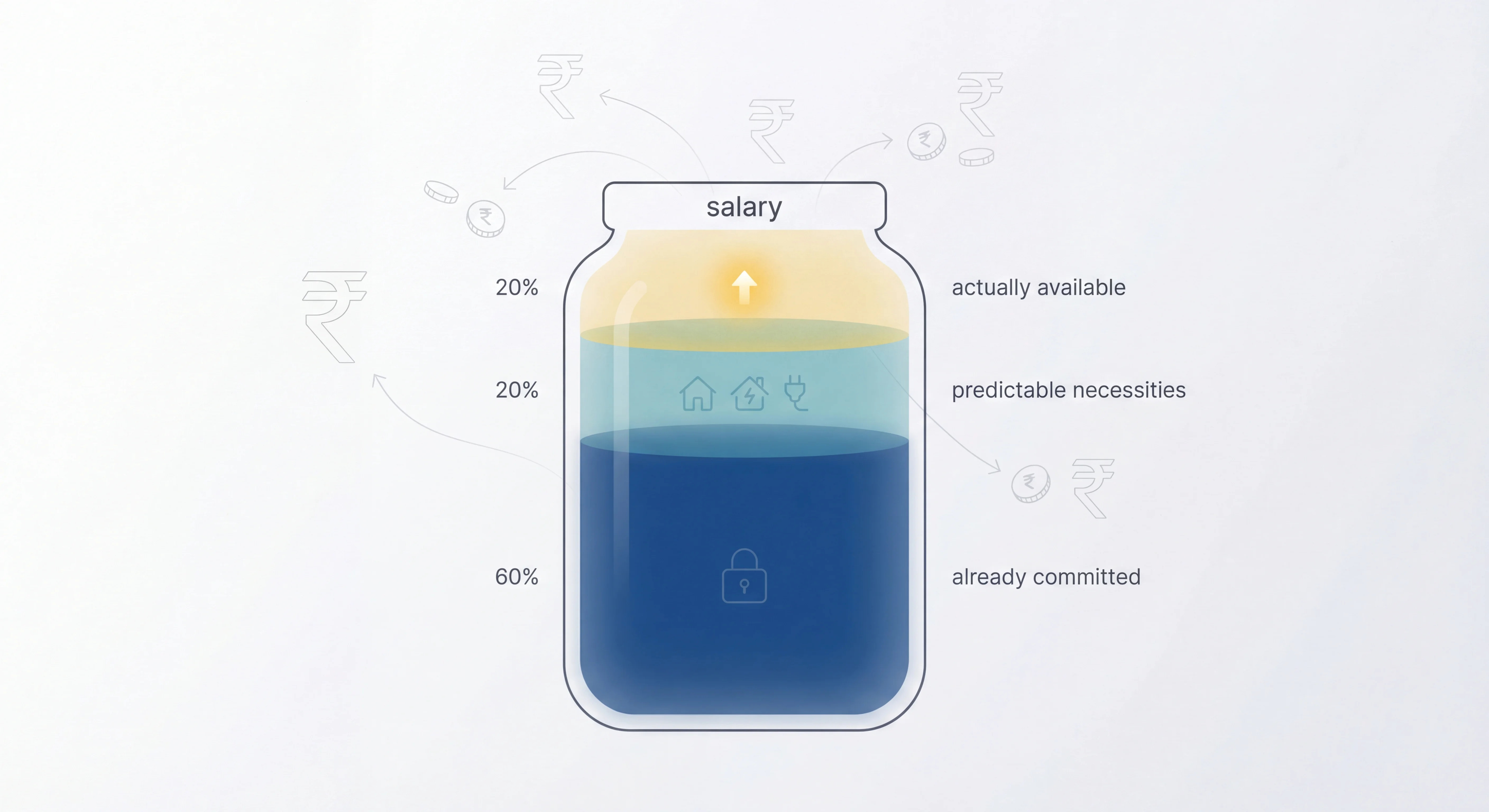

The Real Starting Number

Stop thinking of your salary as "what shows up in your account on payday."

Your actual starting number—the money that's genuinely yours to allocate—is:

Gross Salary minus deductions (PF, tax) minus committed payments (rent, EMIs) minus predictable necessities (groceries, bills, transport) = Discretionary Money

For most people, this final number is 20-30% of the gross salary.

If you earn ₹75,000 gross, you might have ₹15,000 discretionary. That's your real number.

Everything else is spoken for before it arrives.

The First Week Is the Most Dangerous

The window between salary arriving and committed payments leaving is when most financial damage happens.

Because you're operating under the illusion of abundance.

If you can mentally lock that committed money away the moment it arrives, treat it as if it's not yours. The rest of the month becomes much clearer.

Money Isn't Disappearing—It's Following the Path You've Built

Your money goes where you've made it easy to go.

Auto-deductions. Saved payment methods. One-click ordering. Cab apps. Food delivery apps.

Every convenience you've set up is a path your money can flow down without you noticing.

You're not watching it disappear. You've just built a system that makes spending frictionless and saving require effort.

The Question Isn't "Where Did It Go?" It's "What Did I Think I Had?"

The money went where it always goes. To rent, bills, groceries, life, and the things you chose.

The confusion isn't about where it went.

The confusion is about thinking you had ₹75,000 to work with when you actually had ₹15,000.

That gap—between the number that arrived and the number that was available—is why it feels like it disappeared.

What This Connects To

This vanishing-salary pattern is the reason most people can't save. Can't build an emergency fund. Can't invest. Can't plan.

Because if you don't know how much money is actually yours—if you keep overestimating your starting point—you can't allocate anything.

Later, you'll learn to budget. You'll learn to separate money by purpose. You'll learn to create surplus intentionally.

But all of that starts with understanding this:

Your salary isn't what you see on payday. It's what remains after everything that's already committed.

Once you know your real starting number, everything else becomes possible.

This awareness doesn't solve the problem. But it's the beginning of seeing the problem clearly.

And seeing clearly is what makes change possible.

The Pattern You're In

Your salary doesn't disappear by month-end.

It was already mostly gone on day 1. You just didn't realize it because the committed money sat in your account for a few days. It moved to where it was always going to go.

During those few days, you experienced a false abundance. You made decisions based on that false abundance. And by the time the committed money left and you saw what was actually available, you'd already spent from the discretionary portion too.

This isn't a failure of discipline. It's a failure of awareness.

You can't manage what you can't see. And you can't see what you're measuring incorrectly.

The shift isn't about spending less or earning more.

It's about knowing your real starting number.

And once you know it—once you stop being surprised every month by the same pattern—you can start making different choices.

Not because you should. Not because anyone told you to.

But because you finally see what's actually happening.

Actionable

The Real Starting Number Exercise

This is simple but revealing. You'll need: Your last salary slip or bank statement showing salary credit, a piece of paper or your phone's notes app, and 10 minutes of honesty.

Observation List:

- 1Write down the number

- 2Subtract what's already committed

- 3Subtract predictable necessities

- 4Sit with this number

Step 1: Write down the number

What amount actually hit your account on payday? (Not gross salary—actual credit amount)

Let's say it's ₹68,000.

Step 2: Subtract what's already committed

Go through the next 7 days of your bank statement and note every payment that:

- Happens automatically (rent, EMI, SIP)

- Would happen whether you thought about it or not (insurance premium)

- You have no choice about (credit card minimum due)

Add these up. Let's say it's ₹42,000.

Subtract this from your salary: ₹68,000 - ₹42,000 = ₹26,000

Step 3: Subtract predictable necessities

Now think about the month ahead. What do you know you'll spend on?

- Groceries (roughly)

- Electricity bill (roughly)

- Phone/internet

- Fuel or metro card

- House help salary

- Children's school supplies/tuition

These aren't fixed-date payments, but they're not optional. Estimate conservatively.

Let's say it's ₹11,000.

Subtract: ₹26,000 - ₹11,000 = ₹15,000

Step 4: Sit with this number

₹15,000.

This is your real starting number. Not ₹68,000. Not even ₹26,000.

₹15,000 is what's actually available for everything else across the entire month.

Now answer these questions (just for yourself):

- When you got paid, what number were you mentally working with?

- What's the gap between that number and your real starting number?

- Does this gap explain why the month feels so tight by day 20?

- Have you been making decisions based on the wrong starting point?

The insight:

Don't try to fix anything yet. Don't feel bad about the number being smaller than you thought.

Just notice the gap.

Notice the difference between what you thought you had and what you actually had.

That gap is where the confusion lives.

LEARNING OUTCOME:

This exercise builds the critical skill of accurate mental accounting—knowing your true starting position instead of the illusory one. Most people operate all month with a number in their head that was never real, which is why they're constantly surprised by scarcity. This exercise reveals the gap between perceived money and available money. Once you see this gap clearly, the mystery of "where did it go" evaporates. It didn't disappear—you just started from the wrong number. This awareness is foundational: you can't budget, can't save, can't plan until you know what you're actually working with. The power isn't in the number being bigger or smaller—it's in knowing the real number and making decisions from there.

Smit Panchal

Chartered Accountant | Writing about Money, Clearly

Smit simplifies complex money concepts through first-principles thinking and real-world insights. Writing on personal finance, wealth frameworks, and financial clarity—beyond noise, products, and hype. Views expressed are personal and educational.

Connect on LinkedIn